This is the story of three dictators. Two of them are Pakistanis. The third one is a Bengali.

This is the story of three dictators. Two of them are Pakistanis. The third one is a Bengali.

All of them have an affinity with the month of March. And all of them have played havoc with lives, the first two in Pakistan in the times before the emergence of Bangladesh, the last one in Bangladesh quite some years into the liberation of the country.

In the history of Pakistan and Bangladesh, men rising to power on the strength of coups d’etat— and you can certainly include here a fourth dictator, the first one to subvert constitutional rule in Bangladesh — have been a sordid part of life.

The Pakistanis were the self-styled Field Marshal Mohammad Ayub Khan and General Agha Mohammad Yahya Khan. The Bengali was Lieutenant General Hussein Mohammad Ershad. The fourth, or that first military ruler in Bangladesh, Lieutenant General Ziaur Rahman, was of course not associated with March. But beginning in March 1976, by which time he had already seized power (and that was in November of the previous year), he launched a concerted programme of falsifying and distorting Bangladesh’s history. But that is a different story, to be told another day.

Let us return to Ayub Khan. On 25 March 1969, unable to withstand the pressure of the mass upsurge against his decade-long rule in Pakistan, he decided to call it a day. The public expectation was that he would hand over power to Abdul Jabbar Khan, the Speaker of the National Assembly, in line with the constitution he and his cohorts had imposed on the country in 1962. He simply turned his back on his own constitution, cast it to the winds, and handed over power to General Yahya Khan, the commander-in-chief of the Pakistan army (it would not be until the Bhutto years that the title ‘commander-in-chief’ would be replaced with ‘chief of staff’).

Of course, Ayub Khan did not wish to leave office, which he had been effectively in control of since 27 October 1958, when he forced Major General Iskandar Mirza into exile. Having called a round table conference bringing the regime and the political opposition together in negotiations in February 1969, Ayub agreed to return Pakistan to parliamentary democracy. That was not enough for the opposition, in both East and West Pakistan. The masses wanted him to go. For his part, he expected Yahya Khan to assist him in imposing a second martial law in the country and have him run things as he had run them for ten-plus years.

And that was the moment for Yahya Khan to step in. Having waited impatiently since early 1968, when Ayub fell seriously ill and Yahya ran the show from behind the thick curtains of government, he now wanted the President to leave. Remember Yahya Khan was among the senior military officers — the others being Generals Burki. K.M. Shaikh, et cetera — sent by Ayub to Mirza on 27 October 1958 to order him at gunpoint to resign and hand over full powers to Ayub. On 25 March 1969, Yahya Khan saw power within his reach. He compelled Ayub Khan to resign and pass on the presidency to him.

On 25 March 1969, martial law was indeed declared all across Pakistan. But the new chief martial law administrator was Yahya Khan, not Ayub Khan. Thus did Pakistan’s first military ruler take leave of power and the second have his writ imposed on the country. The next day, General Yahya Khan told the nation in a broadcast — and this he did in the morning — that his goal was to create conditions conducive to the restoration of democratic government in Pakistan. Over the months that followed, he appeared to be working in line with popular desires. His regime, unlike Ayub’s, did not place any political leader under arrest. He went around meeting leading politicians in both East and West Pakistan, impressing them with his sincerity in relation to the restoration of democracy in the country.

Yahya Khan decreed the end of the One Unit system in West Pakistan, thereby restoring the four provinces of Sindh, Punjab, Baluchistan and North-West Frontier Province (today’s Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa) to their old, historical forms. He allocated seats in the future national assembly on the basis of population in the federating units of Pakistan. He put in place a Legal Framework Order relating to the elections and the framing of a new constitution for the country. Restrictions on political activities were lifted on 1 January 1970, with general elections set for October of the year, which date was subsequently shifted to December owing to the devastating floods in East Pakistan. The rest is, of course, a litany of everything which Yahya Khan pushed into going wrong. Already a tenuous state because of the inherent weaknesses of its foundations, Pakistan went through severe convulsions under Yahya following the elections. His refusal to honour the results of the elections, his initiation of genocide in what had by then been transformed to Bangladesh, the arrest of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his farce of a trial by the regime, his launch of a war against India were soon to push him to the ropes. He presided over the break-up of Pakistan and was forced from office on 20 December 1971 in humiliation. Placed under house arrest by President Z.A. Bhutto, he was freed from it when General Ziaul Haq seized Pakistan in July 1977. He died in August 1980.

The rest is, of course, a litany of everything which Yahya Khan pushed into going wrong. Already a tenuous state because of the inherent weaknesses of its foundations, Pakistan went through severe convulsions under Yahya following the elections. His refusal to honour the results of the elections, his initiation of genocide in what had by then been transformed to Bangladesh, the arrest of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his farce of a trial by the regime, his launch of a war against India were soon to push him to the ropes. He presided over the break-up of Pakistan and was forced from office on 20 December 1971 in humiliation. Placed under house arrest by President Z.A. Bhutto, he was freed from it when General Ziaul Haq seized Pakistan in July 1977. He died in August 1980.

Our third dictator, General Hussein Muhammad Ershad, began to acquaint Bengalis with his political ambitions in a not so subtle way when he began speaking publicly of the need for a national security council soon after the presidential election of November 1981 that elevated Justice Abdus Sattar to the top job in the country. Clear signs began to emerge of Ershad’s growing insubordination to the President, leading to a bad climax on 24 March 1982 when he mounted a coup against Sattar. It was an unprovoked coup given that an elected President and an elected parliament were in place. Illegitimacy was back in politics.

General Ershad ruled for nearly nine years. In the manner of Ayub Khan, who formed the Convention Muslim League; in the manner of Ziaur Rahman, who cobbled the Bangladesh Nationalist Party into shape, Ershad gave form to the Jatiyo Party. He called fraudulent elections in 1986, tried breaking up the High Court into several segments, permitted Bangabandhu’s assassins to form a political party, pushed the country further into communal politics and, again like Ayub and Zia, seduced a number of prominent politicians into ditching principles and linking up with him.

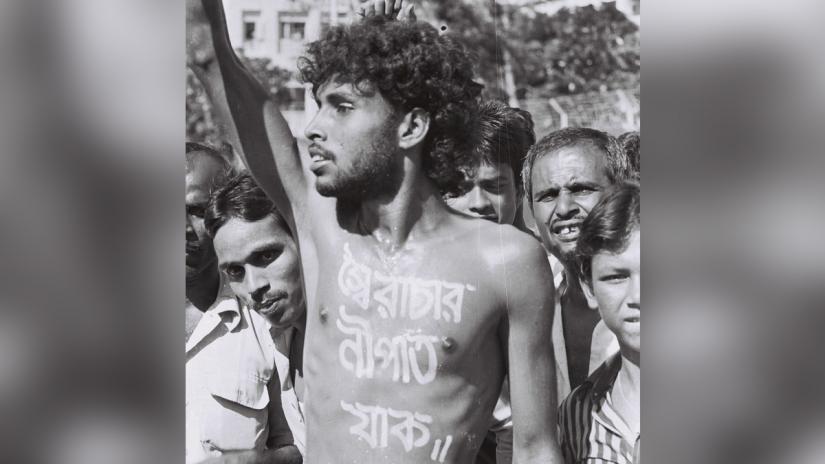

If on 25 March 1969 it was a mass upsurge which compelled Ayub Khan to quit power, on 6 December 1990 it was a similar popular movement which drove Ershad from office.

Ayub Khan was never to return to public life after March 1969. Yahya Khan lived in disgrace after December 1971. In contrast, Hussein Muhammad Ershad survived and has gone on playing a role in Bangladesh’s politics, to the consternation of citizens.

And yet the truth must not be looked away from.

27 October 1958, 25 March 1969 and 24 March 1982 are dark episodes in the recent history of our part of the world.

These were days which spawned dictators, in the way 5 July 1977 and 12 October 1999 gave people Ziaul Haq and Pervez Musharraf in Pakistan; in the way 7 November 1975 pushed Bangladesh into terror when Ziaur Rahman commandeered the state.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is the editor in charge at the Asian Age.