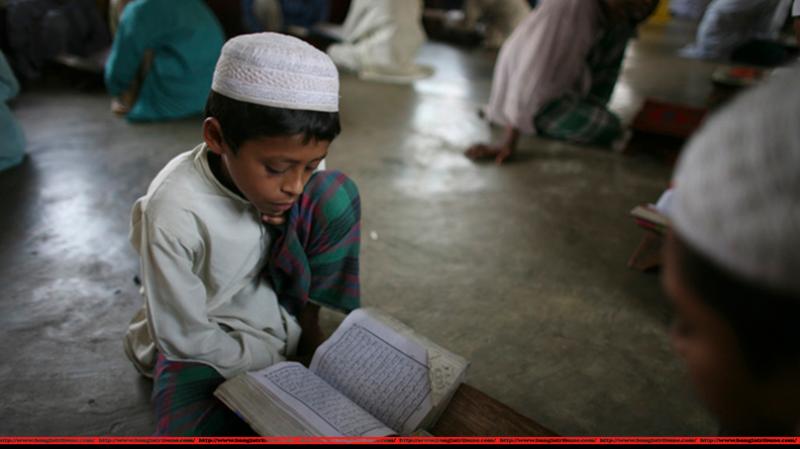

The third part of a six-part series which takes an in-depth look inside Bangladesh’s madrasa education system.

The third part of a six-part series which takes an in-depth look inside Bangladesh’s madrasa education system.

Despite having two kindergartens near his house, Mohammad Moshiur Rahman, a 33-year-old madrasah teacher in Gazipur, sent his elder son to the same Islamic seminary where he works.His two other children – a boy and a girl – are also awaiting admission to the madrasah.

“My son is completing his Nurani course (taught at the Ebtedayee or primary level) and in future, he will be enrolled in the Hifz course (for memorizing the Quran),” Moshiur said.

He says he believes that the recommendation by a Hafiz (one who has learned the Quran by heart) will earn a Muslim a place in heaven.

When asked why he chose madrasah education for his son, Moshiur said, “I sent him there so that he is rewarded by the grace of Allah. Moreover, traditional education will be useless in the afterlife. That is why I chose madrasah-based education.” Many people associated with madrasahs and mosques hold the same perception as Moshiur, particularly in the rural areas.

The number of parents linked to mosques and madrasas, who send their children for general education at the beginning of their academic life, is small. Other than religious motivation, one of the reasons why people choose madrasahs is because they cost less compared to schools.

Professor Abul Barkat, the author of Political Economy of Madrasah Education in Bangladesh published in 2011, says that more than half of the students come from poor and lower-income families. According to the research presented in the book, 44% of madrasah students came from middle-income families and the rest from upper middle class and affluent families (5.2%).

At least 10 people, interviewed by the Dhaka Tribune, defended their decision to send their children to madrasahs but said that in most cases madrasah graduates struggled to earn Tk 5,000 a month. Apart from the monthly wage at the mosque, madrasah graduates usually make up to Tk500 by teaching Arabic and Quran, conducting a special prayer ceremony, or reciting the Quran.

Leading Taraweeh prayers during the Ramadan is another way of earning some extra money for the Imams, they said. But the money is usually not enough to maintain a family with children.

A handful of children from such families, however, get the scope to go to high school after passing their Ebtedayee (primary-level madrasah education) exams and then on to colleges. Students from these families are rarely seen studying at universities.

All the interviewees said they sent their children to madrasahs to save educational expenses.

“At boarding madrasahs education is free. Madrasah authorities charge a minimal amount for food and accommodation. For the orphans, it is free of cost. Other kids also get discount — maybe half of the fees,” said Mawlana Rafiqul Alam, principal of Gazipur’s Monshipara Hafijiya Madrasah and Etimkhana (orphanage). Prof Barkat’s research showed that larger families tend to send their children to madrasahs. These big families want at least one of the children to receive education in the religious stream.

Prof Barkat’s research showed that larger families tend to send their children to madrasahs. These big families want at least one of the children to receive education in the religious stream.

There is also a common belief among the majority of the low-income families in Bangladesh that madrasah teachers are more caring. These families also have negative or misconception about the secular education system. This encourages them to send their children to the madrasahs.

Another reason the interviewees gave for choosing madrasah education was to send mischievous sons to residential madrasahs to help them become ‘good human beings’.

“My parents were frustrated as I was not the obedient type. My mother suggested enrolling me at a nearby madrasah. They thought teachers there would bring me under strict control,” said Abdullah, now a Dhaka University student. “I found the madrasah teachers more caring about the students”, he added.

“This is particularly true for the boarding madrasah teachers,” Abdullah said. “Most of the teachers have families in their village home. And so, the teachers spend most of the time with the students. Their guidance is strict, according to my experience.”

In some cases, madrasah teachers also influence the parents to send their children to their educational institutions.

“Those who want to work for Allah generally send their children to madrasahs,” said Mawlana Rafiqul Alam.

Hailing from Mymensingh, Rafiqul said, “Parents contact me when their children continue to disobey them. So, I suggest them to get their children enrolled in madrasahs in order to guide them properly.”

Community ties among the residents of a certain locality also promote madrasah education, he observed.

There are also some exceptions where affluent and educated families plan madrasah education for their children, the reporters’ findings show.

Various types of madrasahs, currently operating in Bangladesh, actually impart modern education alongside the Arabic lessons and religious subjects, thanks to the timely measures by the madrasah authorities.

Cadet madrasahs, kindergarten madrasahs, and even separate girls’ madrasahs are among the more progressive types.

“I wanted my child to start his education amid religious spirit. So I sent him to a madrasah,” said a guardian of a student at Muhammadia Makjunul Ulum Madrasah in Uttara. They teach not only Arabic but standard English too.

“From here we may shift him to an English medium school,” the parent said, adding the expenses at the madrasah was almost same as an English medium school.

This article was first published in dhakatribune.com