Pakistan’s former prime minister Nawaz Sharif has finally made it to London. Life for him has been quite a mess in the last few years, with all those charges of corruption brought against him by the establishment. He has lost his wife to cancer. He has been in prison and he has seen his political party pushed into the backwaters by his country’s army, which decided at one point to make it possible for Imran Khan to take charge of Pakistan. In jail, Sharif’s health deteriorated, necessitating his treatment abroad.

Pakistan’s former prime minister Nawaz Sharif has finally made it to London. Life for him has been quite a mess in the last few years, with all those charges of corruption brought against him by the establishment. He has lost his wife to cancer. He has been in prison and he has seen his political party pushed into the backwaters by his country’s army, which decided at one point to make it possible for Imran Khan to take charge of Pakistan. In jail, Sharif’s health deteriorated, necessitating his treatment abroad.

The Pakistan government ought not to have put up impediments in his way. But when it demanded that he sign a bond and leave seven billion rupees as a guarantee that would return to Pakistan in four weeks, it went for overreach. Now that Nawaz Sharif has finally left the country, thanks to the intervention of the judiciary, the Imran Khan government has been left red in the face. And yet politics of this rather low nature is not new in Pakistan. Sharif himself remains guilty of trying to prevent then army chief Pervez Musharraf from landing back in Karachi after a conference he had attended in Colombo in October 1999.

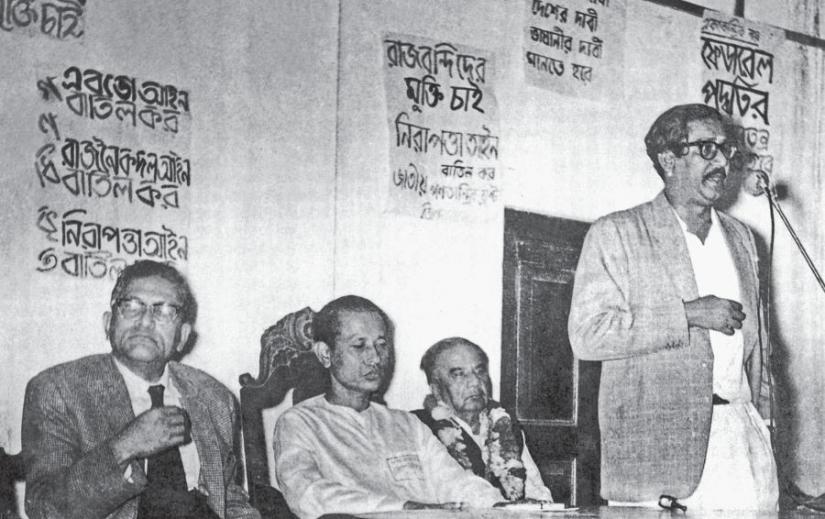

Politics in Pakistan has in its history often been pushed into hostage-like conditions. One remembers only too well the efforts expended by the regime of Field Marshal Mohammad Ayub Khan to induce Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman into taking part in the round table conference he called in February 1969. The efforts fell flat when the Bengali leader, then in prison in connection with the Agartala Conspiracy Case, insisted on his unconditional release before he would agree to travel to Rawalpindi. And that precisely was what happened. Bangabandhu went to the RTC a free man.

There are other stories, political in nature, we recall from those old times. When President Iskander Mirza was pushed out of the government only twenty days after he and Ayub Khan had together imposed martial law in Pakistan in October 1958, he was forced into exile in Britain. Mirza lived for nearly eleven years after his ouster from power and died in London in November 1969. His family made fervent appeals to President Yahya Khan, who had seized power from Ayub Khan in March of the year, that Mirza’s remains be allowed to be buried in Pakistan. Yahya, who had been one of the officers sent by Ayub to secure Mirza’s handover of power to him, and that too at gunpoint, did not agree.

Iskander Mirza was eventually buried in Tehran through the efforts of Ardeshir Zahedi, then Iranian foreign minister and son-in-law of the Shah. In his times, General Ziaul Haque went out of his way to prevent Benazir Bhutto’s return to Pakistan in the mid-1980s but in the end, had to give way. Back in 1979, once Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had been sentenced to death in a controversial case for murder, the Libyan and Saudi governments made it known that they were ready to have the former prime minister live in exile in either Tripoli or Riyadh without indulging in politics, Zia refused. His constant worry was that somehow someday Bhutto would make a re-entry into politics and make sure that his nemesis, in this case, Zia, paid the price for his crime of having violated the constitution. Bhutto was conveniently sent to the gallows.

Iskander Mirza was eventually buried in Tehran through the efforts of Ardeshir Zahedi, then Iranian foreign minister and son-in-law of the Shah. In his times, General Ziaul Haque went out of his way to prevent Benazir Bhutto’s return to Pakistan in the mid-1980s but in the end, had to give way. Back in 1979, once Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had been sentenced to death in a controversial case for murder, the Libyan and Saudi governments made it known that they were ready to have the former prime minister live in exile in either Tripoli or Riyadh without indulging in politics, Zia refused. His constant worry was that somehow someday Bhutto would make a re-entry into politics and make sure that his nemesis, in this case, Zia, paid the price for his crime of having violated the constitution. Bhutto was conveniently sent to the gallows.

But Bhutto himself has the reputation, despite being a civilian politician, of having been the most fearsome of leaders Pakistan has had. He respected no one and brooked no interference with his political ambitions, as 1971 was to prove so well. In the early 1960s, as foreign minister in the Ayub regime, Bhutto held out the threat that Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, who had moved into exile in Beirut following his release from prison, would not be permitted to return to the country. Suhrawardy was to die in Beirut in December 1963.

Speaking of the hostage politics which has often defined the scene in Pakistan, there is the disturbing tale of the Elective Bodies’ Disqualification Ordinance (EBDO) promulgated by Ayub Khan soon after his seizure of power. It was his way of ensuring that the politicians he had silenced remained in that state through offering guarantees that they would stay away from politics. The firebrand young politician Sheikh Mujibur Rahman refused to offer any such guarantees.

Speaking of the hostage politics which has often defined the scene in Pakistan, there is the disturbing tale of the Elective Bodies’ Disqualification Ordinance (EBDO) promulgated by Ayub Khan soon after his seizure of power. It was his way of ensuring that the politicians he had silenced remained in that state through offering guarantees that they would stay away from politics. The firebrand young politician Sheikh Mujibur Rahman refused to offer any such guarantees.

Of course the future founder of Bangladesh paid the price not once, not twice, but many times over. When he was transferred by the police to the army in December 1967 once the Agartala charges were framed, he was not seen or heard from until the day when his trial, along with those of his co-accused, commenced in the Dhaka cantonment in June 1968. His sufferings were to be worse in 1971. Here he was, elected majority leader of the Pakistan national assembly and the country’s prospective prime minister, in solitary imprisonment a thousand miles from home. No one knew of the proceedings initiated against him before a military tribunal; no one knew that he had been sentenced to death.

There are too the stories of the sufferings endured by Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, G.M. Syed, Khan Abdul Wali Khan and Abdus Samad Achakzai.

The rest is history.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is the author of biographies of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Tajuddin Ahmad and writes on politics and diplomacy.