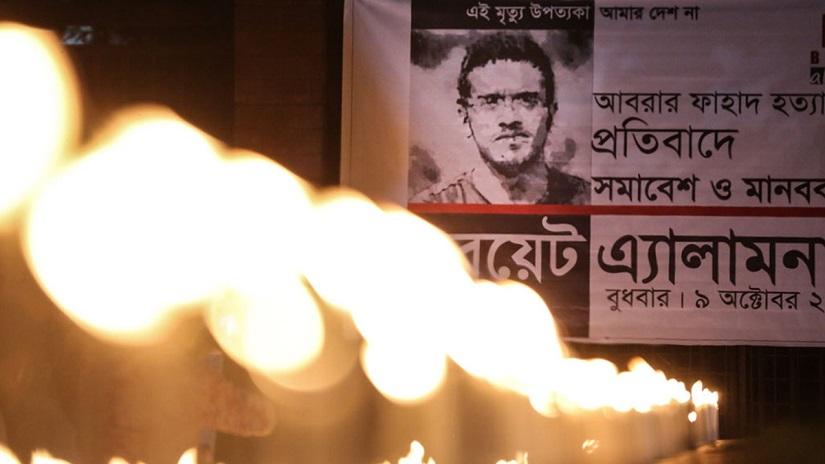

A few days ago, a senior leader of the Bangladesh Chhatra League made it known that the organization would not take responsibility for the murder of Abrar Fahad at the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology. The implication was that the tragedy had been the doing of individuals who incidentally were part of the Chhatra League and therefore the organization could not be held accountable for their behaviour.

A few days ago, a senior leader of the Bangladesh Chhatra League made it known that the organization would not take responsibility for the murder of Abrar Fahad at the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology. The implication was that the tragedy had been the doing of individuals who incidentally were part of the Chhatra League and therefore the organization could not be held accountable for their behaviour.

Such an assertion was wrong, morally as well as politically. The young men who beat Abrar Fahad to death did so from a sense of impunity, from an awareness that they belonged to the student front of the ruling Awami League and therefore were beyond the pale of the law. It is that coarseness which coursed through their criminality as they bludgeoned Abrar to death. The Chhatra League would have earned the sympathy of the people if its leadership had publicly taken responsibility for the criminal act of its people at Buet and had unreservedly apologised to the country.

Men and women who take moral responsibility for wrongs committed by people on their watch or for wrongs they commit on their own are people who know the meaning of decency, who are emblematic of integrity. And organizations which move fast in punishing the black sheep among them, along with expressing contrition for the sins and crimes of the black sheep, are groups not willing to deviate from the higher calling of life. It is a truth which sadly did not trouble the Vice Chancellor of Buet. He has made it clear that he did not commit any wrong and therefore he saw little reason to resign. He chose to ignore the shame of Abrar’s murder happening on his watch, indeed of the many lapses in behaviour of the Chhatra League even as he occupied the high office of Vice Chancellor.

There have been precedents for individuals to acknowledge moral responsibility for a bad situation and walk away from the scene with their dignity intact. Not very long ago, Prof Anwar Hossain, unable to withstand the agitation of the teachers of Jahangirnagar University against him, tendered his resignation from the position of Vice Chancellor and left the campus. The act enhanced popular respect for him.

In similar fashion, Dr Atiur Rahman, as Governor of Bangladesh Bank, found himself mired in controversy generated by the digital heist of the bank’s foreign exchange reserves in the United States. He did not hang on to his position but took the moral route: he resigned and went home.

In early 2007, Gen Hasan Mashhud Chowdhury, Akbar Ali Khan, Sultana Kamal and CM Shafi Sami, having reached the conclusion that they could not morally continue being part of the caretaker administration headed by President Iajuddin Ahmed, walked away from their position as advisors. There are times when individuals in high office feel unable, either physically or morally, to carry out their responsibilities with satisfaction to themselves. President Abu Sayeed Chowdhury informed Bangabandhu in late 1973 that he wished to leave office. He was as good as his word.

There are times when individuals in high office feel unable, either physically or morally, to carry out their responsibilities with satisfaction to themselves. President Abu Sayeed Chowdhury informed Bangabandhu in late 1973 that he wished to leave office. He was as good as his word.

And it was not the first time that Justice Chowdhury had the morality factor working in him. In March 1971, away in Geneva to represent Pakistan at a human rights conference, he lost little time in repudiating the state of Pakistan when news came to him of the killings of teachers and students of Dhaka University, where he was Vice Chancellor, by the Pakistan army. He moved to London, to represent the Bangladesh cause before the world. In August 1975, Foreign Minister Kamal Hossain, on an official visit in Europe, learned of Bangabandhu’s assassination while he was in Belgrade. Despite all blandishments by the usurper regime of KhondokarMoshtaq, he did not return home. It was an ethical position he adopted, for all the right reasons.

And so we have these instances of decent men strengthening our belief in the ability of societies to power themselves to the future through an adherence to principles and dignity. And yet there have been all those others who did not or would not have the courage to step down from their high pedestals when they should have. In August 2004, Khaleda Zia could have demonstrated immense moral courage had she chosen to resign from the office of Prime Minister in the aftermath of the grenade explosions at an Awami League rally. She and her government not only did not apologise to the nation for the tragedy taking place during their time in office but also tied themselves in knots by trying to build a false narrative around the killings.

Some years ago, the minister for disaster management in the Awami League government would not dream of stepping down from office when it became known that his son-in-law had become embroiled in the seven-murder case in Narayanganj. His position was untenable and public respect for him plunged steeply. The food minister, faced with the scandal of bad wheat being exported from abroad, saw little need for him to resign. He hung on to his job. Likewise, the finance minister of the time, having loudly voiced his opposition to black money being converted to white, ended up doing exactly what he had been opposing. He had all that ill-gotten money translated into legal currency. A far better option for him would have been to resign.

Deference to public opinion and consciousness of self-esteem are characteristic of men steeped in the nuances of liberal democracy. That is the lesson coming down to us in modern times.

In 1956, Indian railway minister Lal Bahadur Shastri resigned in the aftermath of a train accident. Years later, in 1999, Nitish Kumar, faced with a similar tragedy as railway minister, took himself out of office.

In March 1971, Lt Gen SahibzadaYaqub Khan, martial law administrator, and Vice Admiral SM Ahsan, governor of East Pakistan, unwilling to throw morality to the winds by continuing to be part of the power structure at a time when the Yahya Khan regime was on its way to undermining the election results of December 1970, resigned and flew back to West Pakistan.

In April 1969, French President Charles de Gaulle, having vowed to quit office if he lost the constitutional referendum he had called, lived up to his promise when voters rejected his reform proposals.

In May 1974, Willy Brandt, taking full responsibility, resigned from the position of Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany when a communist mole was discovered in his office.

In recent years, entrepreneurs in South Korea and Japan, caught in business-related scandals, have apologized to the public and have resigned, giving themselves up to the law in the interest of investigations into their crimes.

We in Bangladesh have the will and the capacity to give to ourselves a democratic system properly empowered to respond to our needs. The system we envisage will fundamentally rest on the ability of men and women to lead the process of a strengthening of the institutions that are the pillars of the state, that can resist any and all attacks on them from any quarter.

But, first, we need to have men and women in whom the light of moral courage shines; in whom burns a fire which impels them into serving citizens without fear or favour or prejudice; in whom the readiness is there to acknowledge wrong when they commit wrong and who will then make their way to the exit of their own volition.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is the author of biographies of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Tajuddin Ahmad and writes on politics and diplomacy.

Opinion

Opinion

41112 hour(s) 31 minute(s) ago ;

Evening 07:25 ; Wednesday ; Jun 25, 2025

Responsibility, resignations ... and individuals of moral courage

Send

Syed Badrul Ahsan

Published : 17:00, Oct 13, 2019 | Updated : 17:25, Oct 13, 2019

Published : 17:00, Oct 13, 2019 | Updated : 17:25, Oct 13, 2019

0 ...0 ...

/pdn/

Topics: Top Stories

***The opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the opinions and views of Bangla Tribune.

- KOICA donates medical supplies to BSMMU

- 5 more flights to take back British nationals to London

- Covid19: Rajarbagh, Mohammadpur worst affected

- Momen joins UN solidarity song over COVID-19 combat

- Covid-19: OIC to hold special meeting

- WFP begins food distribution in Cox’s Bazar

- WFP begins food distribution in Cox’s Bazar

- 290 return home to Australia

- Third charter flight for US citizens to return home

- Dhaka proposes to postpone D8 Summit

Unauthorized use of news, image, information, etc published by Bangla Tribune is punishable by copyright law. Appropriate legal steps will be taken by the management against any person or body that infringes those laws.

Bangla Tribune is one of the most revered online newspapers in Bangladesh, due to its reputation of neutral coverage and incisive analysis.

F R Tower, 8/C Panthapath, Shukrabad, Dhaka-1207 | Phone: 58151324; 58151326, Fax: 58151329 | Mob: 01730794527, 01730794528