For those who are in their mid-forties and above, the period between 1982 and 1990 was marked by socio political turbulence, upheavals, non-stop hartals (shutdowns) and curfews.

For those who are in their mid-forties and above, the period between 1982 and 1990 was marked by socio political turbulence, upheavals, non-stop hartals (shutdowns) and curfews.

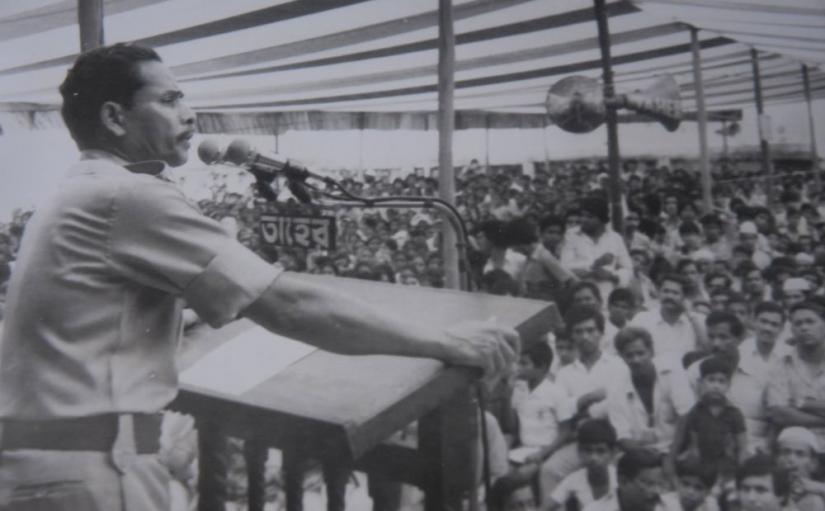

The country at that time, went through convulsions; a dictator was in power and young protestors clamouring for democracy were on the roads.

Today I see many tributes being paid to HM Ershad, who was once the autocrat at the head of our country. At that time, we were growing up as the first generation in an independent nation facing ubiquitous restraints.

The moment I think of Ershad, I visualize a revolution of the people, long before the Arab Spring happened, as the people of Bangladesh united to rise against a ruler who took over power by force.

No doubt, as ruler of the country, Ershad had done a lot of development work. Many people remind me from time to time that under him, the first Bangladeshi peace mission went for UN peacekeeping missions, major roads were built, Friday declared a holiday and so on, but here’s my belief: what is important is how one goes to power because once someone is on the throne, the reforms and the development automatically happen as part of state operation. Some do a lot, others do less but when one is in power, a sense of benevolence comes naturally.

Aurangzeb, the last of the great Mughals, came to power over the blood of his brothers and riding on ruthless shenanigans and a deft manipulation of situations. But once on the throne, he ruled pretty much like most of his predecessors, with determination and tenacity. It is no different with many despots in history.

Any conversation about the autocratic period evokes a shambolic scene of our education system of the time. In fact, it was due to the political unrest during the dictatorial period that we now have such a large US-Bangladeshi community.

Whether that’s good or bad is up to the reader to decide.

But the tumultuous political setting of the 80s triggered many social changes which still impact our lives. Sessions jam and educated unemployed

Sessions jam and educated unemployed

This was the second decade after independence; the first decade was also rocked by bloodshed, assassinations, and apocalyptic political changes.

The 80s started with the bloodless takeover by Ershad, which may be the most redeeming side of the putsch.

The protests began soon after and like all social movements, Dhaka University, as the crucible, led the way and suffered the consequences.

Weapons entered the campus in huge numbers and, at one point, there was a rumour that in the residential halls stinger missiles had arrived.

A spectre of death hovered over education with the pen replaced by the Molotov cocktail and the gun.

The strikes, hartals and the raging public movement coalesced into what can be called a people’s revolution. The remnants of the socialist craze in the 1970s indoctrinated the youth into believing that a socialist Utopia is possible.

In between all the frenzy, education suffered. A student entering a public university would be lucky to come out with a degree in seven years. Sometimes, it took eight years to get a Masters’ degree.

It was common to find 27-28 year olds going around, desperately looking for employment. Since THE political arena was volatile, foreign companies, investors shunned Bangladesh.

The picture of the angst -riddled unemployed young man was intertwined with the social creed in such a manner that it influenced popular culture, movies, theatres and literature.

In the restless spirit of the unemployed man and woman, Bangladesh voiced her frustration.

The perturbing image of the forlorn ‘Shikkhito Bekar’ (the educated unemployed) is very much a 80s phenomenon.

Jobs were scarce and the only way out was to give the TOEFL exam, sell the family land and fly to the USA to catch the American dream. Leaving unrest, heading for the land of Stars and Stripes

Leaving unrest, heading for the land of Stars and Stripes

Call it brain drain or a pragmatic step by the meritorious students, 80s youth culture was dominated by politics, TOEFL and the ‘i-20’ from an American college or university.

By the way, if you have forgotten those days or belong to a younger age bracket, i-20 was the acceptance letter from a US academic institution.

While many students took to the streets to protest against the dictatorial regime, a feeling of hopelessness about lingering session jams compelled parents to send their children abroad for education.

At that time, the USA was the preferred destination as ‘Islamophobia’ had not become a major social aberration.

Perhaps I am not wrong in saying that the much used observation ‘Deshe Thaika Ki Hoibo!’ (What can one achieve by staying in the country!) originated in the 80s, when faced with the grim prospect of spending eight years at university and ending up old and unemployed, droves of young people decided to leave the country.

Obviously, most of those who left were highly intelligent and set the basis for the large US-Bangladeshi community that emerged later. This exodus can also be looked at in a positive way but the reality is that many of these students who left Bangladesh to study in the USA, also took their parents later on and over time, their links with Bangladesh became tenuous.

Almost 85 percent of those who went to study during Ershad’s turbulent regime, decided to stay back and make USA their new home.

The unfortunate thing is; these dynamic people could not give their full effort for the development of Bangladesh. Those who stayed to fire a successful revolution!

Those who stayed to fire a successful revolution!

The most iconic image of the violent period is that of democracy activist Noor Hossain with the slogans, ‘Gonotontro Mukti Pak’ (let democracy be free) written on his chest and ‘Shoirachar Nipat Jak’ (down with autocracy) on the back. Noor Hossain was killed while protesting against Ershad on Nov 10, 1987 near Zero Point, later named after him as the Noor Hossain Square.

Like Noor, countless students decided to stay in Bangladesh and carry on the protest. Hartals and strikes were regular with curfew declared at the end of 1987. After 7 pm, all movement on the roads was prohibited and Dhaka became a city of the haunted. In the cold fog of winter, soldiers stood on guard on the streets, their silhouettes in long coats, 303 rifles and steel helmets reminiscent of British troops on guard during the Second World War, as seen in many war films.

And then the fall came on Dec 6, 1990. As I remember distinctly, millions came out on the streets armed with drums, kitchen utensils or anything that could make a lot of noise.

On that day, the nation needed to scream, shout and be noisy to let off steam and celebrate. The demon has been exorcised – read the papers, with BTV going offering special programmes to mark the watershed moment.

The country was in ‘Eid mood’!

For me, who is just as old as the country, the Ershad period brings back memories of relentless political struggles, perennial social malaise, high unemployment, romantic revolutionaries, curfews, the exodus of the young to the USA, maverick poets, rebel writers, renegade film makers and, of course, the painting by famous artist Quamrul Hassan, mocking the autocrat – Desh Aaj Bissho BehAyar Khoppre (The country is now in the hand of the champion of shamelessness).

Rest in peace, dear dictator, it’s because of you we crafted a social revolution which can arguably be called the most successful of all public uprisings.

Towheed Feroze is a news editor at Bangla Tribune and teaches at the University of Dhaka.