Deshbandhu Chitta Ranjan Das saw his life drawing to an end in 1925, more than twenty two years before his beloved India would emerge into tortured freedom in August 1947. His death prompted an outpouring of tributes to him, to his politics and character by such luminaries as Rabindranath Tagore and Mahatma Gandhi. A distraught Subhash Chandra Bose heard about his leader’s death in prison. Something went out of Netaji’s life.

Deshbandhu Chitta Ranjan Das saw his life drawing to an end in 1925, more than twenty two years before his beloved India would emerge into tortured freedom in August 1947. His death prompted an outpouring of tributes to him, to his politics and character by such luminaries as Rabindranath Tagore and Mahatma Gandhi. A distraught Subhash Chandra Bose heard about his leader’s death in prison. Something went out of Netaji’s life.

And yet Subhash Bose would carry the struggle for freedom to newer heights and newer dimensions over the next couple of decades. Of all the men who had worked with Deshbandhu or had cause to sympathise with his politics, Netaji was the one who would come close to achieving the goal of national freedom. Netaji strayed from the constitutional path and deliberately veered off on to a course where he believed armed resistance to the British colonial power was the sole means of ensuring liberty.

To what extent Deshbandhu would agree with his disciple’s methods remains open to question. History does not deal with ‘ifs’ and ‘buts’. Even so, there is the issue of whether Netaji would have taken the course he did had Deshbandhu not died so early on in the struggle for freedom. Again, if imperial Japan had not begun to wobble and finally collapse before the Allied Powers in World War Two, would Netaji actually march into Delhi and take charge of a free India? How would he govern? Would he be a dictator? Or would he, as he said in the course of his struggle, leave it to the people of India to decide the form of government they would be ruled by?

And then comes that all-important question: to what extent would a victory of the Indian National Army prevent or slow down the march of Muslim communalism which had already got underway through the agitation of the All-India Muslim League for a division of the country? Both Deshbandhu and Netaji were committed to the concept of Indian nationalism. It is reasonable to suppose, therefore, that with Netaji taking charge of India at the end of a triumphant INA march to Delhi, the spectre of communalism would have taken a back seat, fundamentally because the British authorities, then busy encouraging the partition of the country, would be in a state of turmoil brought on by military defeat. The defeat did not happen, of course. If it had, who knows what might have followed? And who can tell if Japan’s militarists would have permitted Netaji a free hand to run India? The basic difference which separates Bangabandhu from Deshbandhu and Netaji lies in the fact that where Das and Bose were unable to witness the birth of freedom in India, Mujib was able to lead the Bengalis of a truncated, eastern segment of Bengal to independence from Pakistan. His achievement was unique in that his people went to war for liberty in his absence, for he was in prison in Pakistan, on the strength of his inspirational leadership. Not many in Bangladesh at the time expected Bangabandhu to return to Bangladesh. Indeed, many had feared he would be executed by the military junta of Yahya Khan. But he did return and he did take up the reins of government in a country ravaged by war.

The basic difference which separates Bangabandhu from Deshbandhu and Netaji lies in the fact that where Das and Bose were unable to witness the birth of freedom in India, Mujib was able to lead the Bengalis of a truncated, eastern segment of Bengal to independence from Pakistan. His achievement was unique in that his people went to war for liberty in his absence, for he was in prison in Pakistan, on the strength of his inspirational leadership. Not many in Bangladesh at the time expected Bangabandhu to return to Bangladesh. Indeed, many had feared he would be executed by the military junta of Yahya Khan. But he did return and he did take up the reins of government in a country ravaged by war.

What if Bangabandhu had not been assassinated in his free country? To what extent would he strengthen the democratic process in Bangladesh despite the draconian changes he put in place barely eight months before his murder? Should he have stayed, Gandhi-like, away from a direct exercise of power and let the very capable Tajuddin Ahmad administer the country? It was a tragedy for Bangladesh’s people when Mujib and Tajuddin went their separate paths so early after the country’s liberation. It emboldened the right-wing elements lurking in the bushes, along with their friends outside the corridors of power, who eventually did both men in?

These are questions whose answers, if they were proffered, would be pointless given the circumstances that have already come to pass.

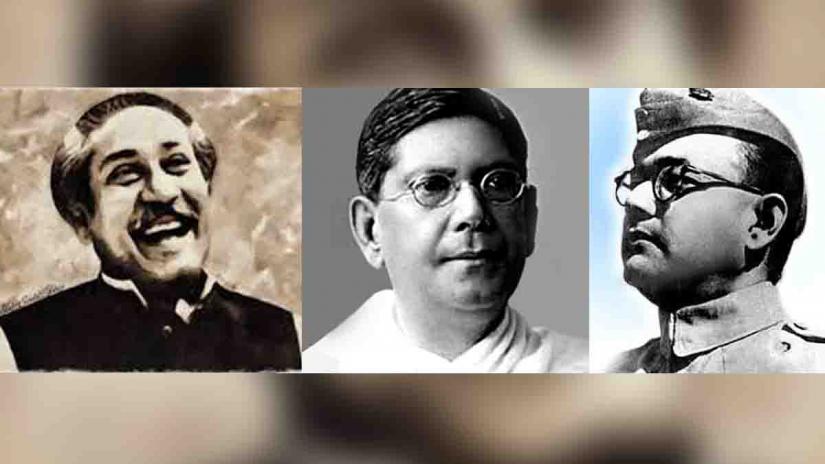

The bigger truth, though, is that these three men --- Deshbandhu, Netaji and Bangabandhu --- were light at the end of the tunnel for Bengalis. They were bold enough to take up the challenges thrown their way and move on, in their distinctive ways, toward attaining their goals. The tragedy of death prevented them from dispensing more of their wisdom than they already had on their people.

Today, Deshbandhu, Netaji and Bangabandhu are part of Bengali folklore. They are remembered in the villages of a Bengal which today remains divided along the lines dictated by the parochial politics of the 1940s. And yet, for all the division, for all the barriers put in place by men whose understanding of history was poor and of culture was poorer, these three men have remained the recipients of paeans to the nobility of the struggles they embodied in their lifetime.

They are the three men of Bengal. They are the pride of Bengalis everywhere --- in Bangladesh, in West Bengal and across the diasporas that stretches all the way from Rabindranath Tagore’s land to the farthest reaches of the earth.

(Deshbandhu died on 16 June 1925; Netaji perished or vanished on 18 August 1945; Bangabandhu was assassinated on 15 August 1975)

Syed Badrul Ahsan is a political commentator and biographer of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Tajuddin Ahmad.