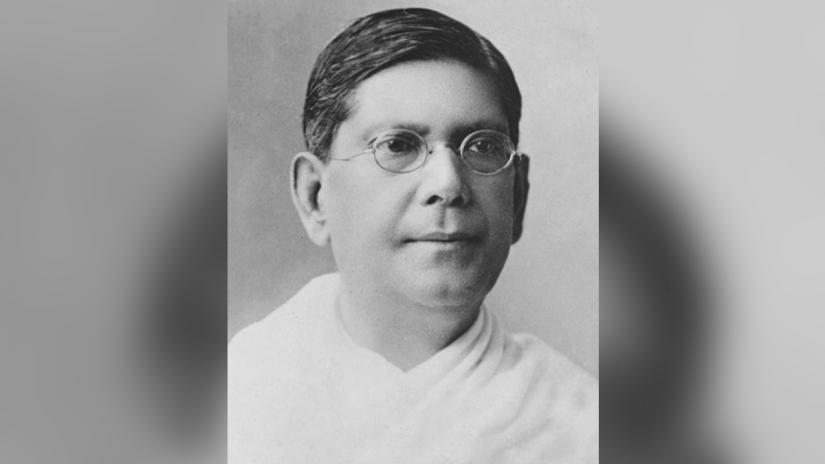

They were all Bengalis, all remarkable men who shaped, in enormity, the destinies of their people. They had a sense of purpose that could only justify the old argument of Bengal reflecting on things a day earlier than what the rest of India would be doing about the self-same things. These three men—two Hindus and a Muslim—were larger than life men whose impact on their societies, indeed on the geographical and political ambience around them, has endured to a degree that has only reinforced their place in history. These three men are Chittaranjan Das, honoured in the Indian subcontinent as Deshbandhu; Subhash Chandra Bose, revered as Netaji; and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, celebrated as Bangabandhu. They led tumultuous lives, the first two in a yet undivided, colonised India, the third in a country that came into being on the basis of religious communalism and therefore had little time or inclination to respect his cultural roots.

They were all Bengalis, all remarkable men who shaped, in enormity, the destinies of their people. They had a sense of purpose that could only justify the old argument of Bengal reflecting on things a day earlier than what the rest of India would be doing about the self-same things. These three men—two Hindus and a Muslim—were larger than life men whose impact on their societies, indeed on the geographical and political ambience around them, has endured to a degree that has only reinforced their place in history. These three men are Chittaranjan Das, honoured in the Indian subcontinent as Deshbandhu; Subhash Chandra Bose, revered as Netaji; and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, celebrated as Bangabandhu. They led tumultuous lives, the first two in a yet undivided, colonised India, the third in a country that came into being on the basis of religious communalism and therefore had little time or inclination to respect his cultural roots.

All three men died relatively young. Das was 55 when death came to him. Bose was a mere 47 when he died, or went missing, in Taipei. Mujib’s life was snuffed out when he was 55. Through a remarkable, uncanny coincidence, all of them met their end in years that ended in the number 5. Das died in 1925, Bose in 1945, Mujib in 1975.

Das’ premature death in 1925 is generally looked upon as a period when the Indian subcontinent commenced its descent into communal politics, a trend that would grow and widen in the times ahead. Having been the most influential force behind the Bengal Pact, Das was clearly on his way to playing a bigger role in the struggle for India’s freedom from British colonial rule. Bengalis have held fast to the notion, however wishful or perhaps misplaced, that had Das lived longer, India might not have had to go the way of partition in the later part of the 1940s.

With Bose is associated the idea of the rebellious Bengali. And yet rebellion was not the way he came into politics. For the better part of his adult life, his loyalty was to constitutional politics, a sign of the political education he had acquired under the tutelage of C.R. Das. His role in the struggle for Indian independence, within the ambit of the Congress, was perhaps nowhere more pronounced than through his election as the president of the party in the late 1930s. And then came the irony. Bose’s re-election as president of the Congress did not please Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. If that was the beginning of disillusion in him, his subsequent incarceration at the hands of the British colonial power cemented his feeling that politics as usual would not persuade the British into leaving India. Armed struggle would. The rest, in the Bose story, is history.

Mujib’s story is somewhat in contrast to Bose’s. Where Bose veered away from constitutional politics in his final years, for Mujib a paramount need was for the Bengali struggle for autonomy within the state of Pakistan to be pursued within the parameters of constitutionalism. Through the 1960s, he remained steadfast in his conviction that Bengali rights could be attained through dialogue with the West Pakistan-based regime, a belief he believed had been vindicated through the massive electoral victory of his party, the Awami League, at Pakistan’s first general elections in December 1970. That belief was set at nought when in an act of perfidy the military regime undermined political negotiations and opted for a programme of systematic genocide through nine months in 1971. It was left to Mujib’s lieutenants to wage, in his absence — for he was a prisoner of the Pakistanis — a war of national liberation which was to culminate in the emergence of a free Bangladesh out of the ashes of East Pakistan.

There are other and finer points about the careers of these three men whose influence on the Bengali psyche has never wavered.

Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das, in his all too brief career, consistently followed the principle of legality and constitutionalism in his endeavour to ensure Swaraj — or self-rule — for India. That Das was the face of the future was a point not lost on Evelyn Thomas, who in the issue of Labour Monthly, Volume 5, in September 1923, noted:

‘Mr. C.R. Das, late President of the All-Indian National Congress, and founder of the Swaraj Party, is the acknowledged successor of Mr. Gandhi as an all-India leader. He has snatched the falling standard and is carrying it forward in the struggle between Indian bourgeois nationalism and British Imperialism — a struggle which is destined to be a long one.’

Das’ life was to come to an end less than two years later. When it did, Gandhi, the man whose successor Thomas had thought Deshbandhu would be, paid a profound tribute to the great man:

‘Deshbandhu was one of the greatest of men ... He dreamed ... And talked of freedom of India and of nothing else … His heart knew no difference between Hindus and Mussulmans and I should like to tell Englishmen, too, that he bore no ill-will to them.’

Subhash Chandra Bose’s tempestuous career veered from the unambiguously constitutional to the riotously rebellious, for his was a clear conviction that British colonial rule needed to be brought to an early, if necessary armed, end. His departure from the Congress and into the Forward Bloc, leading eventually to a concerted struggle for independence through the Indian National Army, forms part of the mystique surrounding the man.

A few years before Netaji left India to wage his war against the British, Bengal’s celebrated poet Rabindranath Tagore sang his own paean to him thus:

‘As Bengal’s poet, I acknowledge you today as the honoured leader of the people of Bengal.’

When Bose resigned from the presidency of the Indian National Congress, Tagore’s appreciation of Netaji’s qualities of leadership was unmistakable:

‘The dignity and forbearance which you have shown in the midst of a most aggravating situation has won my admiration and confidence in your leadership. The same perfect decorum has still to be maintained by Bengal for the sake of her own self-respect and thereby to help turn your apparent defeat into a permanent victory.’

The rise of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as the undisputed leader of the Bengalis in the eastern half of the old province that formed part of Pakistan after 1947 was grounded on his quick evolution from a young communal politician steeped in the Pakistan ideology to a secular voice of the Bengali nation in the 1960s.

Having been an intense worker of the All-India Muslim League in the 1940s as a devoted follower of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, he was quick to grasp the truth after 1947 that Bengali cultural heritage would be under endless threat in communal Pakistan; that secular Bengali nationalism would then be in order. By 1966, his Six-Point plan for regional autonomy demonstrated his emergence from communal politics and towards a secular perception of things.

Five years later, as he crisscrossed East Pakistan to inform Bengalis that his political programme should be looked upon as a referendum on their future, it was clear he had graduated, and remarkably too, into a secular being. By the end of 1971, he would be the founding father of a sovereign Bengali republic in the eastern part of what had once been the province of Bengal in British-ruled India.

Five years later, as he crisscrossed East Pakistan to inform Bengalis that his political programme should be looked upon as a referendum on their future, it was clear he had graduated, and remarkably too, into a secular being. By the end of 1971, he would be the founding father of a sovereign Bengali republic in the eastern part of what had once been the province of Bengal in British-ruled India.

The poet and writer Annada Shankar Ray paid what clearly was the ultimate, lyrical tribute to Mujib:

‘As long as the Padma, Meghna, Jamuna flow on, till then will your name remain etched in the mind, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.’

A day after his release from the Agartala Conspiracy Case in February 1969, a million-strong crowd welcomed Mujib back to freedom at a public rally at the Dhaka race course. The young, firebrand student leader Tofail Ahmed spoke for all Bengalis when he addressed the freed politician in the following terms:

‘You are the leader of Bengal. You are the voice of Bengal. You are our friend, Bengal’s friend. You are our Bandhu, our Bangabandhu.’

Syed Badrul Ahsan is a political commentator and biographer of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Tajuddin Ahmad.