Fifty-three years ago in Lahore, in February 1966, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman — political heir of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, general secretary of the Awami League, former minister and lawmaker and rising Bengali nationalist leader —made public his Six-point programme for regional autonomy for the federating units of Pakistan.

Fifty-three years ago in Lahore, in February 1966, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman — political heir of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, general secretary of the Awami League, former minister and lawmaker and rising Bengali nationalist leader —made public his Six-point programme for regional autonomy for the federating units of Pakistan.

Fifty years ago, in February 1969, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman stood transformed into the pre-eminent leader of the Bengali nation. The future belonged to him.

February thus entered the pages of history as a defining moment for the Bengali nation.

On 22 February 1969, Vice Admiral AR Khan, Pakistan’s defence minister, announced the unconditional withdrawal of the Agartala Conspiracy Case in Dhaka.

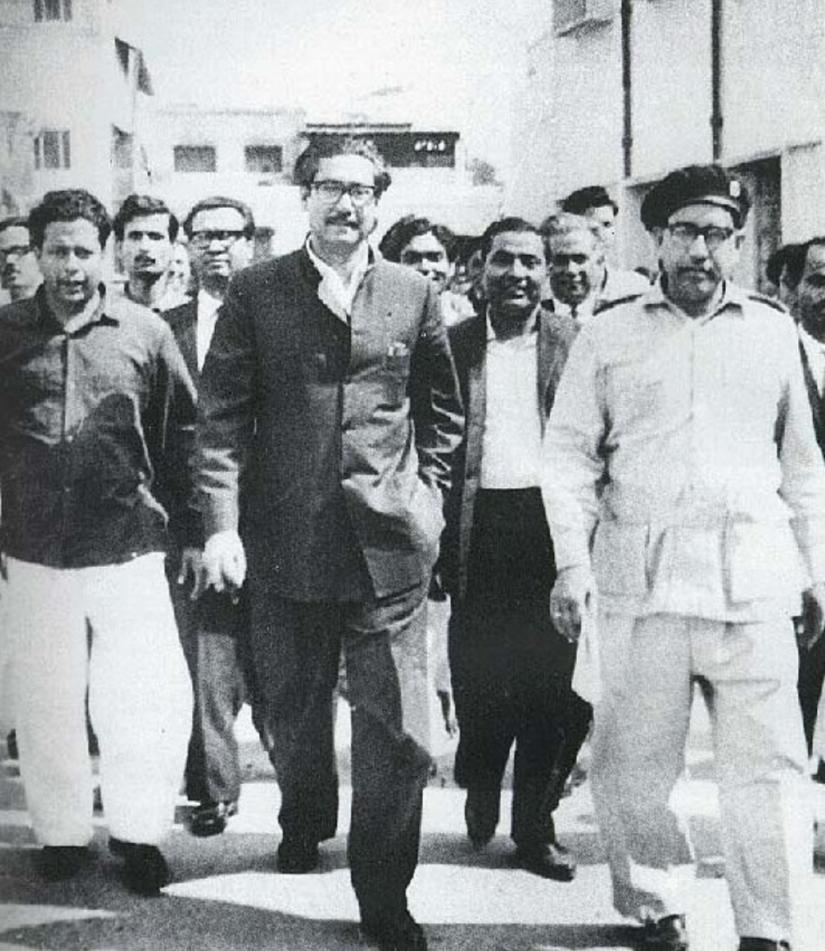

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the leading accused in the case and chief of the All-Pakistan Awami League, walked free from his prison cell in the Dhaka cantonment. He was escorted to his Dhanmondi residence for an emotional reunion with his family. Having been in prison since 8 May 1966 under the Defence of Pakistan Rules, Shiekh Mujib had gone through the trauma of a trial in which he and 34 other Bengalis (men in the armed forces and the civil administration), had been charged with conspiracy to bring about the secession of East Pakistan from the rest of Pakistan through an armed revolt. It was put about by the regime of Field Marshal Mohammad Ayub Khan that Mujib had travelled to Agartala in India to solicit Indian support for his scheme of breaking up Pakistan.

News of the Pakistan government’s ‘unearthing’ of the case first appeared in the media when a sketchy press release late in December 1967 spoke of the arrest of a group of individuals. It was not till early January 1968, however, that the regime formally spoke of what it called a conspiracy that, in its words, had been spearheaded by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Interestingly, Mujib’s name did not figure in the initial list of the accused, leading to suspicions that on second thought and with a view to discrediting the rising Bengali leader the regime inserted his name in the list.

The reaction among Bengalis was one of disbelief. It was generally thought that the whole scheme had been concocted by the Ayub regime to discredit Sheikh Mujib before his fellow Bengalis. Predictably, attention quickly focused on Ayub’s incendiary remarks in 1966, soon after Sheikh Mujib had announced his Six-point plan for regional autonomy within a federal Pakistan in Lahore in February that year. At the time, Ayub had warned that the proponents of the plan would be dealt with in the language of weapons. In West Pakistan, the general masses and the entrenched political classes quickly seized upon the government’s move to decry the attempt to ‘undermine’ the unity and sovereignty of Pakistan. The trial of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his co-accused got underway before a special tribunal in the Dhaka cantonment on 19 June 1968. It was presided over by Justice SA Rehman, a West Pakistani, who was assisted by two Bengali judges, Justice Mujibur Rahman Khan and Justice Maksumul Hakim. A phalanx of defence lawyers, including Britain’s Sir Thomas Williams QC, assisted Sheikh Mujib and his co-defendants. As the trial got underway, Sheikh Mujib told a foreign journalist present in court, “You know, they can’t keep me here for more than six months.” He would miss it by a month. In the seventh month he would be a free man. Meanwhile, all over East Pakistan and then in West Pakistan, political unrest soon began to create tremors.

The trial of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his co-accused got underway before a special tribunal in the Dhaka cantonment on 19 June 1968. It was presided over by Justice SA Rehman, a West Pakistani, who was assisted by two Bengali judges, Justice Mujibur Rahman Khan and Justice Maksumul Hakim. A phalanx of defence lawyers, including Britain’s Sir Thomas Williams QC, assisted Sheikh Mujib and his co-defendants. As the trial got underway, Sheikh Mujib told a foreign journalist present in court, “You know, they can’t keep me here for more than six months.” He would miss it by a month. In the seventh month he would be a free man. Meanwhile, all over East Pakistan and then in West Pakistan, political unrest soon began to create tremors.

Ironically, it was a time when the Ayub Khan regime launched year-long celebrations of its decade in power. Billed as a decade of progress, the celebrations were meant to be a self-adulatory recapitulation of the positive steps the regime had taken since a Coup d'état had placed Ayub in power in October 1958. And yet not everything was as rosy as it was painted out to be. Ayub’s former foreign minister and one-time protégé Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was causing his former benefactor considerable headache. He had formed the Pakistan People’s Party in November 1967 and had declared his intention to seek the presidency at the elections scheduled for 1970. In November 1968, Bhutto, together with the National Awami Party’s Khan Abdul Wali Khan, was arrested by the authorities.

In East Pakistan, political agitation against Ayub Khan scaled increasing fury, with Moulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani leading the movement against President Ayub Khan. As the Agartala case trial wore on, increasing numbers of social and political groups began to voice the demand for its withdrawal and for Mujib to be freed. A worsening political situation forced Ayub Khan, in early 1969, to call a round table conference of political leaders in Rawalpindi. He made contact with Nawabzada Nasrullah Khan, a leading opposition politician from the Punjab, who in turn passed on Ayub’s invitation to other opposition figures. The opposition, united under the umbrella of the Democratic Action Committee, informed the government that Sheikh Mujib needed to be allowed to take part in the round table conference (RTC).

Reports soon began to swirl that Sheikh Mujib, who in the eyes of the government had committed acts of treason against the state of Pakistan, would be freed on parole in order for him to take part in the RTC. But such reports were quickly scotched in Dhaka and Bhashani warned that if Sheikh Mujib were not freed without conditions, Bengalis would march on the cantonment to liberate him. Conditions had already taken a bad turn with the shooting of the young student Asaduzzaman. Motiur, a school student, also succumbed to police firing. In the cantonment itself, Sergeant Zahurul Haq, one of the accused in the Agartala case, was killed by soldiers on the pretext that he had tried to escape from custody. In Rajshahi, the academic Shamsuz Zoha was shot.

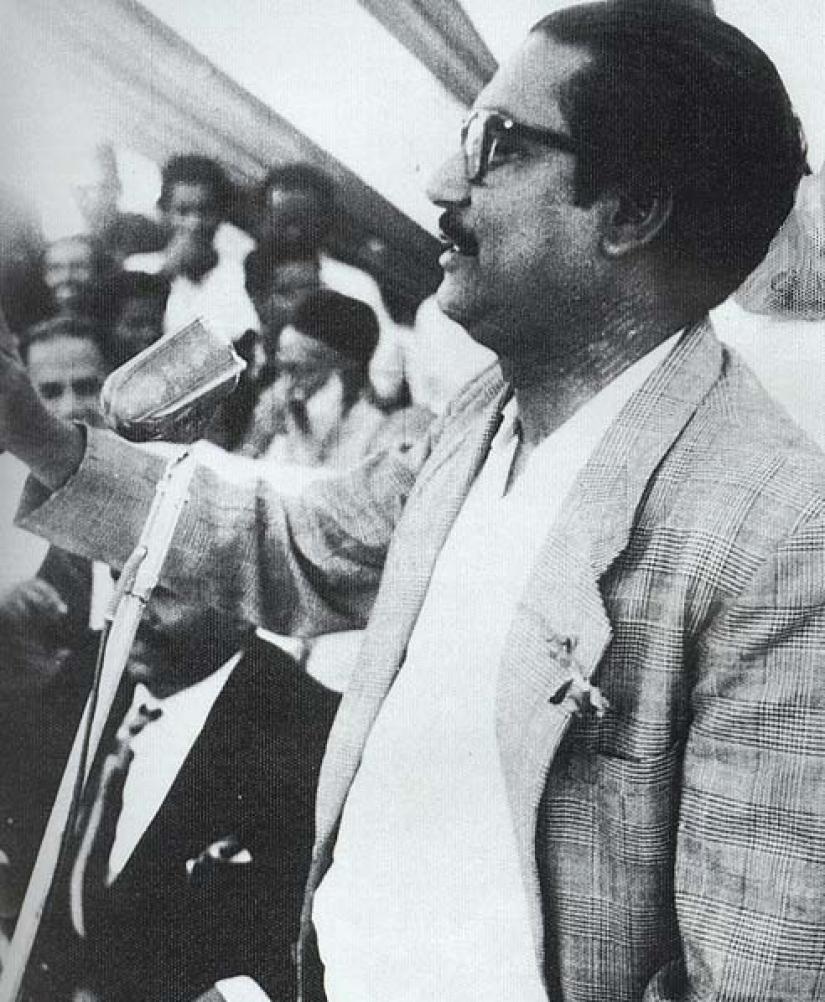

It was popular fury that erupted in East Pakistan by February 1969. Angry crowds of Bengalis overran the residential quarters of Justice S.A. Rehman, who briskly flew off to safety in his native West Pakistan. Politicians across the spectrum demanded that Sheikh Mujib be freed and the case against him be lifted. Young Bengalis, notably university students, banded together with an 11-point programme for radical political change. On 22 February, the case collapsed. The next day, 23 February, Sheikh Mujib addressed a million-strong crowd of Bengalis at the Race Course (now Suhrawardy Udyan) in Dhaka. Student leader Tofail Ahmed, today a senior Awami League politician and former minister, in a rousing speech extolled him as Bangabandhu, friend of Bengal. The new honour accorded to Mujib was accepted by acclamation. On 24 February, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman flew to Rawalpindi as the head of an Awami League team to take part in the round table conference.

On 22 February, the case collapsed. The next day, 23 February, Sheikh Mujib addressed a million-strong crowd of Bengalis at the Race Course (now Suhrawardy Udyan) in Dhaka. Student leader Tofail Ahmed, today a senior Awami League politician and former minister, in a rousing speech extolled him as Bangabandhu, friend of Bengal. The new honour accorded to Mujib was accepted by acclamation. On 24 February, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman flew to Rawalpindi as the head of an Awami League team to take part in the round table conference.

Exactly five years to the day after Bangabandhu was freed from military custody on 22 February 1969; two years and two months after the surrender of the Pakistan army in Bangladesh on 16 December 1971, and two years and one month after the Father of the Nation, by then President of Bangladesh, was freed from solitary confinement in Pakistan by the government of President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto on 8 January 1972, the Islamic Republic of Pakistan accorded diplomatic recognition to the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, on 22 February 1974.

The next day, Prime Minister Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman travelled to Lahore to attend the summit of the Organisation of Islamic Countries (OIC). At Lahore airport, Bangabandhu was welcomed by Pakistan’s President Chaudhry Fazle Elahi and Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. As a band of the Pakistan army played Amar Shonar Bangla, General Tikka Khan, then Pakistan’s army chief of staff and in March 1971 the man who had initiated the genocide of Bengalis in Dhaka and ordered Bangabandhu’s arrest, saluted Bangladesh’s founding father.

History was intensely at work.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is Editor-in-Charge, The Asian Age.

Opinion

Opinion

30841 hour(s) 15 minute(s) ago ;

Evening 08:10 ; Tuesday ; Apr 23, 2024

February: Lahore 1966 ... Lahore 1974

Send

Syed Badrul Ahsan

Published : 17:03, Feb 03, 2019 | Updated : 17:18, Feb 06, 2019

Published : 17:03, Feb 03, 2019 | Updated : 17:18, Feb 06, 2019

0 ...0 ...

/hb/

Topics: Syed Badrul Ahsan

***The opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the opinions and views of Bangla Tribune.

- KOICA donates medical supplies to BSMMU

- 5 more flights to take back British nationals to London

- Covid19: Rajarbagh, Mohammadpur worst affected

- Momen joins UN solidarity song over COVID-19 combat

- Covid-19: OIC to hold special meeting

- WFP begins food distribution in Cox’s Bazar

- WFP begins food distribution in Cox’s Bazar

- 290 return home to Australia

- Third charter flight for US citizens to return home

- Dhaka proposes to postpone D8 Summit

Unauthorized use of news, image, information, etc published by Bangla Tribune is punishable by copyright law. Appropriate legal steps will be taken by the management against any person or body that infringes those laws.

Bangla Tribune is one of the most revered online newspapers in Bangladesh, due to its reputation of neutral coverage and incisive analysis.

F R Tower, 8/C Panthapath, Shukrabad, Dhaka-1207 | Phone: 58151324; 58151326, Fax: 58151329 | Mob: 01730794527, 01730794528